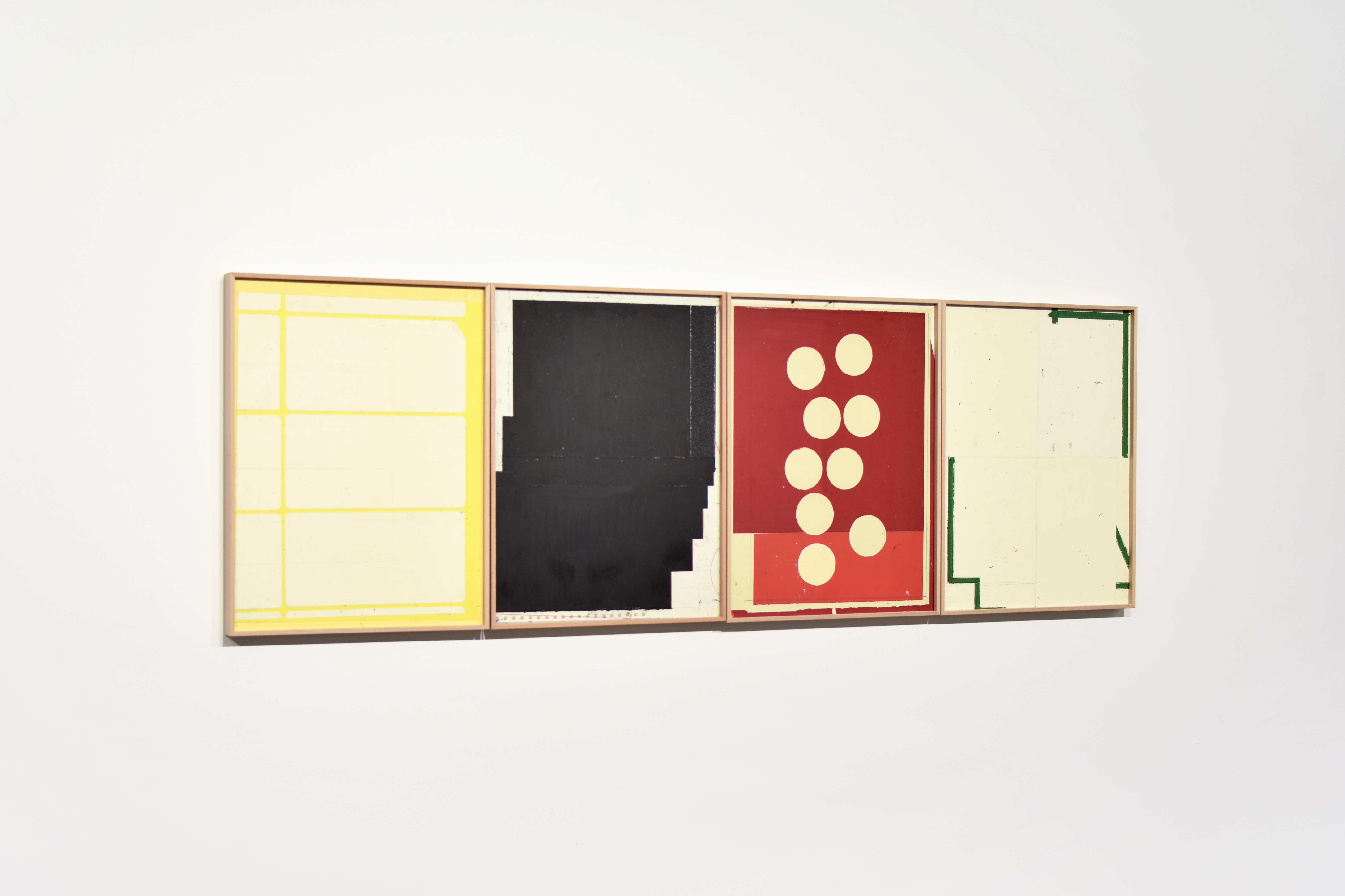

TODOS LOS CAMINOS

TEST, EL CONVENT

ESPAI D’ART, VILA-REAL 2024

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

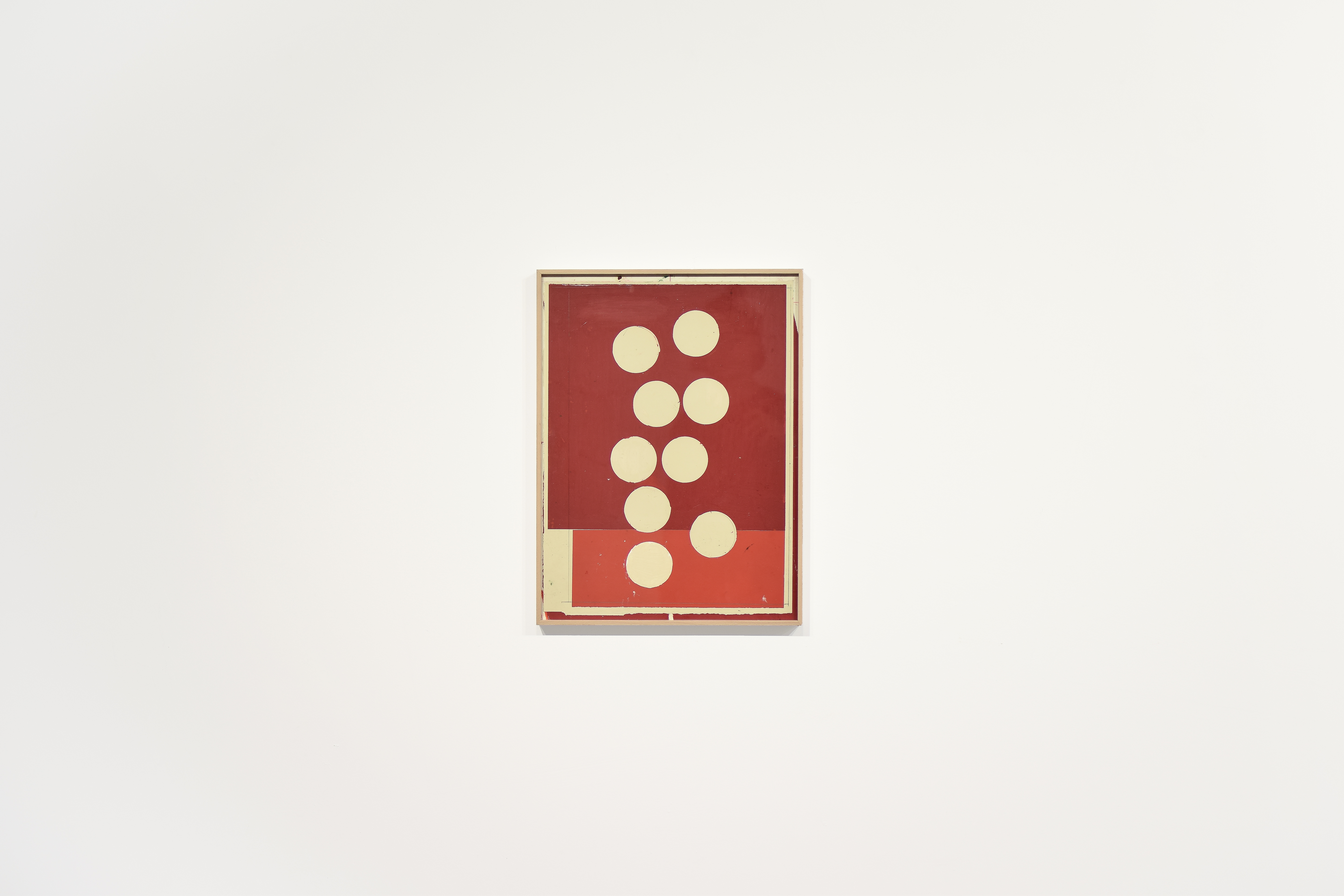

Todos los caminos

Tengo que confesar que El arcoiris de la gravedad es un libro que no he leído. Lo he intentado y no he podido. Me echa, me escupe, me repudia, se ríe de mí una vez y otra y otra. Sin embargo me fascina. Es complicado, inaccesible, punk, críptico, histórico, tecnológico y analógico todo en uno. Os diría de qué va, pero no tengo mucha idea, así que diré que va de cohetes, concretamente del cohete V2 que desarrolló Werner Von Braun para dejar Londres hecho una ruina. De las muchas portadas de este libro, la que más me gusta y la culpable de que lo comprase, es una que tiene los bocetos del V2 en blanco sobre un fondo color azul de Prusia. Esto literalmente en inglés se llama “blueprint” y en español cianotipo.

Todos los caminos es un elegante conjunto de cianotipos que giran en torno a un proyecto que nunca fue. Todos unidos forman una caterva de pistas dejadas como miguitas de pan para un detective extraño que buscase desentrañar el porqué del arte de Ponce, pero estaríamos equivocados si pensásemos que el pintor lo pone fácil. En lugar de ser la narrativa fragmentada en forma de virutas de una obra maestra oculta, Todos los caminos es un conjunto de restos. Restos no como los fragmentos de poca importancia que deja un todo, sino más bien como restos mortales de una belleza seductora. Como reliquias funerarias. Como la escultura brutal y abstracta que forma una montaña de cascotes de ladrillo después del Blitz.

Es mucho más bonita la idea de leer un libro que su propia lectura. Un libro sin abrir es todos los libros posibles. La fantasía de un proyecto por empezar es siempre más agradable que su desarrollo, las posibilidades son infinitas. Tsundoku es como llaman los japoneses a la compulsión de acumular libros sin leerlos. En el mejor prefacio de todos los tiemposAnne Carson habla de que el enamoramiento es exactamente esto. Habla del filósofo protagonista de La peonza de Kafka, que se deleita persiguiendo las peonzas con las que juegan unos niños una y otra vez solo para encontrarse un vulgar trozo de madera en la mano cada vez que las coge. Su vida es un pasar constantemente de la ilusión quimérica de atrapar lo intangible a la náusea que le produce el resultado real. Amamos las metáforas mientras giran, pero no soportamos su explicación. Nos fascina la búsqueda del conocimiento, pero el conocimiento en sí es peor que la investigación. No podemos atrapar la belleza para diseccionarla como a un sapo en una clase. Lo que nos gusta de verdad es perseguirla constantemente sin llegar a alcanzarla. Por eso estamos enamorados de enamorarnos. Por eso Todos los caminos entendido como estelas del pasado o como bocetos del porvenir es mucho más cautivador de lo que lo sería la matriz de la que se desprendieron los fragmentos o la conclusión a la que se podría llegar.

Las conclusiones de la razón no son siempre agradables. El sueño de la razón produce monstruos decía Goya y viendo ciertos refinamientos de la técnica es difícil no estar de acuerdo. Una explosión termonuclear, el exterminio fordista de un grupo humano o lograr sintetizar gas sarín para soltarlo en el metro son sin duda grandes logros de la técnica y la razón, pero no son nada de lo que sentirse orgulloso. La diferencia entre una granada y un reloj suizo es que el segundo no mata y por eso lo llamamos artesanía. La idea de una bomba es más bonita que su realidad. El arte no mata.

En principio.

Emily Dickinson escribió “I died for beauty” en su poema sin nombre 448. ¿Qué va a matarte de belleza sino el arte? El arte de Ponce de momento no mata, pero es difícil no ver en su propuesta el cianotipo, el boceto, la planificación de un proyecto ciclópeo, ajeno a toda medida e incomprensible, del que solo pueden verse fragmentos de lo que queda, retazos descartados de lo que pudiese haber sido o, más terriblemente, destellos de lo que será.

El hecho de que Todos los caminos sea una distorsión fragmentaria, un reflejo en un espejo roto, es precisamente el motivo por el cual podemos mirarlo frente a frente. De no ser así, de no ser el reflejo de un reflejo, de no ser el residuo de algo más grande sino la cosa en sí, probablemente nos convirtiese en piedra como la mirada de Medusa o nos causara un escalofrío como el que sentimos al contemplar los 14 monolíticos metros de un V2. No por nada estos cohetes estaban pintados a secciones blancas y negras como si el mismo Ponce los hubiese intervenido. El arte mata.

“A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.”

Albert Alcañiz

-

All the paths

I have to confess that Gravity's Rainbow is a book that I have not read. I have tried and I have not been able to. He throws me out, he spits on me, he disowns me, he laughs at me again and again and again. However, it fascinates me. It's complicated, inaccessible, punk, cryptic, historical, technological and analog all in one. I'd tell you what it's about, but I don't have much of an idea, so I'll say it's about rockets, specifically the V2 rocket that Werner Von Braun developed to leave London in ruins. Of the many covers of this book, the one I like the most and the reason I bought it is the one that has the V2 sketches in white on a Prussian blue background. This literally in English is called “blueprint” and in Spanish cyanotype.

All Paths is an elegant set of cyanotypes that revolve around a project that never was. All together they form a bunch of clues left like breadcrumbs for a strange detective who sought to unravel the reason for Ponce's art, but we would be wrong if we thought that the painter makes it easy. Rather than being the fragmented, shaving-like narrative of a hidden masterpiece, All the Roads is a collection of remains. Remains not as the unimportant fragments left by a whole, but rather as mortal remains of seductive beauty. Like funerary relics. Like the brutal and abstract sculpture that forms a mountain of brick rubble after the Blitz.

The idea of reading a book is much more beautiful than reading it itself. An unopened book is all possible books. The fantasy of a project to start is always more pleasant than its development, the possibilities are endless. Tsundoku is what the Japanese call the compulsion to accumulate books without reading them. In the best preface of all time, Anne Carson talks about how falling in love is exactly this. It talks about the philosopher protagonist of Kafka's Spinning Top, who delights in chasing the spinning tops that children play with over and over again only to find a vulgar piece of wood in his hand every time he picks them up. His life is a constant transition from the chimerical illusion of capturing the intangible to the nausea that the real result produces. We love metaphors as they spin, but we can't stand their explanation. We are fascinated by the search for knowledge, but knowledge itself is worse than research. We cannot capture beauty to dissect it like a toad in a classroom. What we really like is to constantly chase it without reaching it. That's why we are in love with falling in love. That is why All the paths understood as steles of the past or as sketches of the future is much more captivating than would be the matrix from which the fragments were detached or the conclusion that could be reached.

The conclusions of reason are not always pleasant. The dream of reason produces monsters said Goya and seeing certain refinements of technique it is difficult to disagree. A thermonuclear explosion, the Fordist extermination of a human group or managing to synthesize sarin gas to release it in the subway are undoubtedly great achievements of technology and reason, but they are nothing to be proud of. The difference between a grenade and a Swiss watch is that the latter does not kill and that is why we call it craftsmanship. The idea of a bomb is prettier than its reality. Art doesn't kill.

In principle.

Emily Dickinson wrote “I died for beauty” in her unnamed poem 448. What is going to kill you with beauty if not art? Ponce's art does not kill at the moment, but it is difficult not to see in his proposal the cyanotype, the sketch, the planning of a cyclopean project, alien to any measure and incomprehensible, of which only fragments of what remains can be seen, discarded scraps. of what could have been or, more terrifyingly, glimpses of what will be.

The fact that All the paths is a fragmentary distortion, a reflection in a broken mirror, is precisely why we can look at it face to face. If this were not the case, if it were not the reflection of a reflection, if it were not the residue of something greater but rather the thing itself, it would probably turn us into stone like Medusa's gaze or cause us a chill like the one we feel when contemplating the 14 monolithic meters of a V2. Not for nothing were these rockets painted in black and white sections as if Ponce himself had intervened in them. Art kills.

“A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.”

Albert Alcañiz