UN ENSAYO SOBRE EL ESPACIO

MUVIM, VALENCIA 2023

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Tentar el espacio / Tentar el arte

“Desde el espacio, con su hermano el tiempo, bajo la gravedad insistente, sintiendo la materia como un espacio más lento, me pregunto con asombro sobre lo que no sé” Eduardo Chillida.

Escritos En el Discurso del método (1637), René Descartes estableció las bases de la ciencia moderna como una ruptura respecto de la retórica escolástica. De manera resumida planteó, entre otras cuestiones, que cuando uno se adentra en un terreno desconocido, digamos un bosque del que no conocemos los límites, debe evitar dar vueltas sin sentido y hacer camino en línea recta hasta dar con los límites. Es decir, la ciencia debe delimitar su campo de estudio y progresar de forma tentativa, a base de ensayo y error. En cierto sentido, esto implica que para avanzar en el conocimiento se debe prestar atención a la metodología antes que a los resultados de una investigación.

Ese carácter tentativo de la ciencia se vio reforzado cuando ya en el siglo XX, aparecieron la teoría de la relatividad y la física cuántica, superando el sentido taxativo de la física clásica, la newtoniana y los límites del espacio euclídeo. Esto coincidió históricamente con la aparición y el desarrollo de las vanguardias modernas en el arte. Con los dadaístas, el arte superó los límites de lo físico y lo perdurable. Con una dimensión performativa, propusieron un arte desmaterializado e introdujeron el factor tiempo en el arte, que se convirtió así en algo procesual y efímero. Si se cuestionaban las leyes de la ciencia, ¿por qué no iban a cuestionarse las convenciones de la estética y los cánones de la belleza? El arte tiene en común con la ciencia que no presenta dogmas, no hay verdades absolutas -aunque se apunte a ellas-; es siempre tentativo y, desde una perspectiva histórica, provisional y proliferativo.

Con la posmodernidad se acentuó el interés por los procesos de manera generalizada. Después de una acción, de cualquier manifestación efímera, lo que queda es el documento como registro de un proceso de trabajo. Este interés por los procesos, por el día a día, llevó a un artista como Joan Cardells a elogiar el esfuerzo ensimismado, casi ritual, de artesanos o pintores domingueros sin pretensiones.

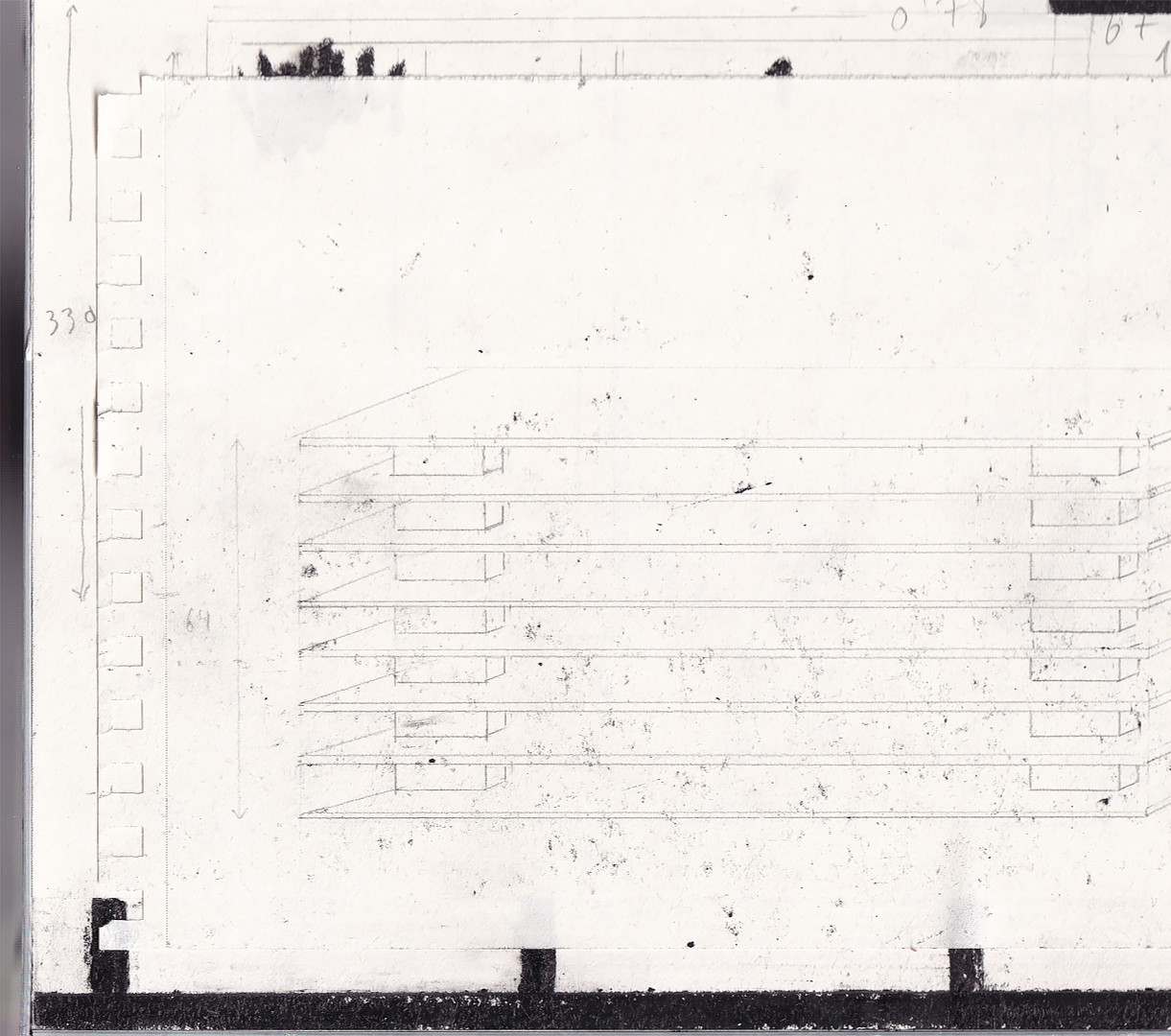

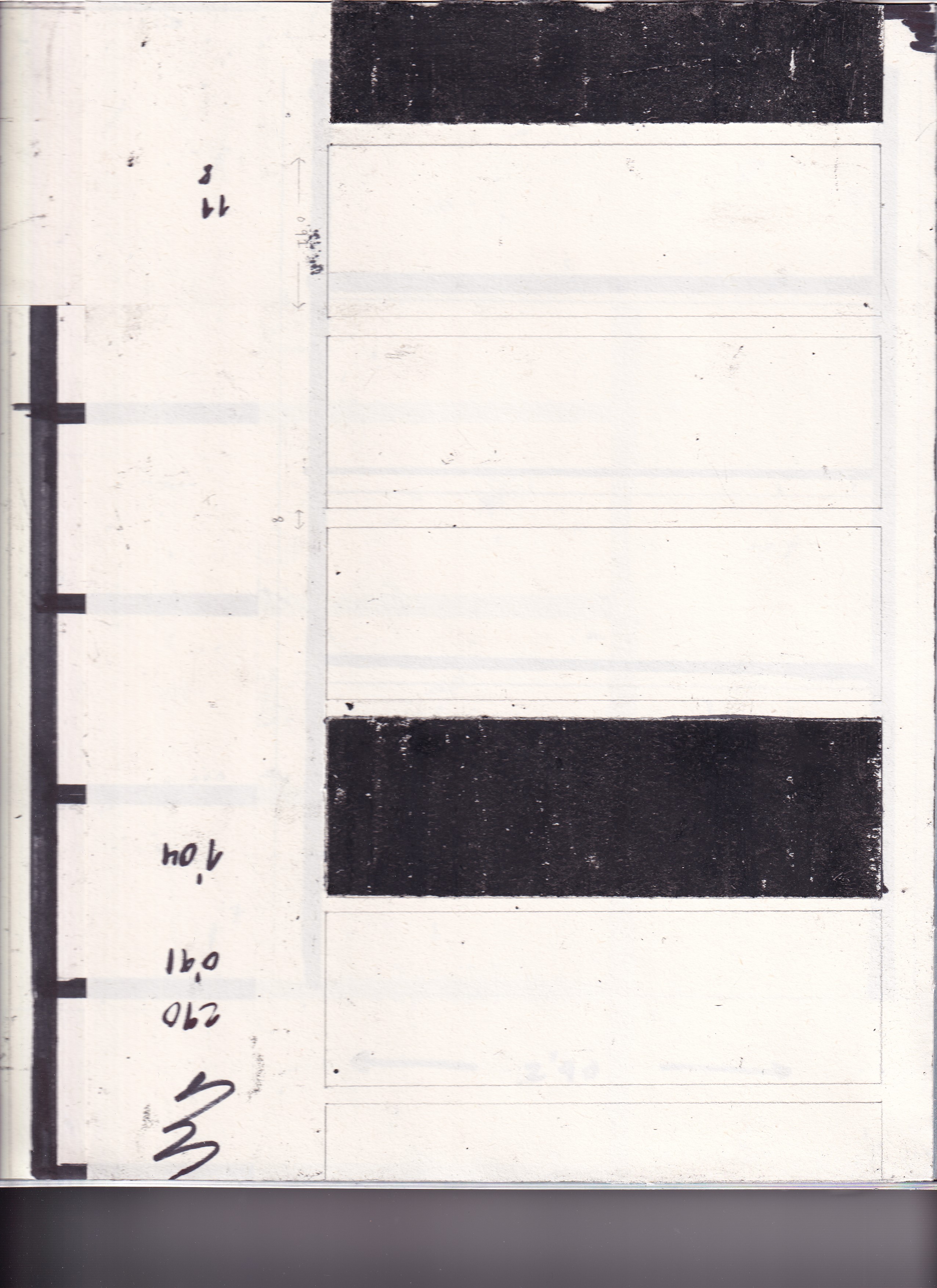

Miquel Ponce nos propone en El cub una mirada a sus procesos de trabajo. Plantea este proyecto como un reto respecto del lugar, como una instalación para un emplazamiento específico, que incluye piezas acabadas –que tienen entidad de obra en sí- y elementos de pruebas y ensayos con diversos materiales de los considerados pobres, típicamente propios de bocetos y trabajos preparatorios. Estos elementos se articulan en el cubo atendiendo a las características particulares del espacio, buscando los límites para definir un espacio que no es físico, sino metafísico, que explora las condiciones de posibilidad de la existencia del arte mismo.

Atendiendo a la naturaleza especulativa del cubo de cristal, la instalación propone una mirada furtiva al estudio del artista en lo que constituye una escena simulada, como una escenografía teatral que incorpora elementos de la tramoya. Es una simulación que permite entrever los entresijos del trabajo y convierte el proyecto en una obra; algo por otra parte característico en el trabajo de Ponce. Pero además, en cierto sentido, se produce un “pliegue” deleuziano cuando el artista muestra como obra una escenificación de su proceso de trabajo.

Entre las múltiples lecturas que ofrece el trabajo de Miquel Ponce, cabe destacar la acepción que él mismo apunta de ensayo como campo de juego y recordar que la noción de juego, tal como lo propone Friedrich Schiller en sus Cartas sobre la educación estética del hombre (1794), ha sido determinante desde el origen en el desarrollo del arte moderno. Schiller proponía que en la ascensión dialéctica hacia la forma más pura de la belleza, la “forma de una forma”, el arte debe desentenderse de la reproducción mimética de las formas de la naturaleza y jugar con las formas propias del lenguaje del arte. El arte abstracto produce formas más puras que el imitativo. Pero cuando el artista se sumerge en un juego y se deja llevar por las formas de su lenguaje plástico sin buscar una forma definitiva -como es el casode Ponce- se aproxima a la forma suprema de la belleza, pues la forma de una forma contiene en sí todas las formas posibles; esto es, define las condiciones de posibilidad de la existencia de una forma.

Por otra parte, resulta estimulante identificar en el trabajo de Ponce un amplio y variado abanico de referencias diversas a diferentes artistas que le interesan de manera muy sincera y sin prejuicios. En el dominio formal podemos establecer relación con los valencianos Amparo Tormo, Ángel Macip o Jorge Carla. En el trasfondo se intuye la influencia de autores de la escuela vasca de los noventa, como Txomin Badiola, Peio Irazu, Jon Mikel Euba o Francisco Ruíz Infante; incluso cierta sintonía remota con Sergio Prego. Pero también están presentes el catalán Miquel Mont o la serie de pinturas en blanco y negro de Miguel Ángel Campano. Asimismo vislumbramos el peso de artistas del ámbito internacional como Robert Ryman, Ad Reinhardt o Imi Knoebel, por ejemplo, y encontramos en la manera de trabajar con los materiales una sensibilidad afín a algunos pintores abstractos de los sesenta como Gerardo Rueda o Rafael Canogar; incluso asoma en la distancia la fuerza en crudo de Manolo Millares.

En su “ensayo sobre el espacio”, Miquel Ponce presenta su trabajo como un ejercicio y juega con las distintas acepciones y matices de la palabra ensayo para definir la mejor manera posible de intervenir en el espacio del cubo del Muvim, de representar sus inquietudes e integrar el espacio en la misma obra. El ejercicio es reflexivo y no pretende aportar una solución única y definitiva. Un músico, un actor o cualquiera, sabe que en ocasiones el ensayo es mejor que la representación final. Lo paradójico es que, a pesar del empeño por explorar el sugerente carácter provisional de las cosas, la obra de Miquel Ponce tiene el mismo aplomo con el que cae, por ejemplo, la manzana de un árbol.

Boye Llorens Peters

-

To Tempt Space / To Tempt Art

"From space, alongside its brother time, under the persistent gravity, feeling matter as a slower space, I wonder with amazement about what I do not know." Eduardo Chillida.

In his work "Discourse on the Method" (1637), René Descartes laid the foundations of modern science as a departure from scholastic rhetoric. In a nutshell, he posited that when one ventures into unknown territory, let's say a forest whose limits are unknown, they should avoid aimless wandering and forge a straight path until they reach the boundaries. In other words, science should delimit its field of study and progress tentatively through trial and error. In a certain sense, this implies that to advance in knowledge, one must pay attention to methodology before the results of research.

This tentative nature of science was further reinforced in the 20th century with the advent of the theory of relativity and quantum physics, surpassing the categorical sense of classical physics, Newtonian physics, and the limits of Euclidean space. This historically coincided with the emergence and development of modern avant-garde movements in art. With the Dadaists, art transcended the boundaries of the physical and the enduring. With a performative dimension, they proposed dematerialized art and introduced the element of time into art, turning it into something procedural and ephemeral. If the laws of science were being questioned, why not challenge the conventions of aesthetics and beauty? Art shares with science the absence of dogma, the absence of absolute truths - though it may aim for them; it is always tentative and, from a historical perspective, provisional and proliferative.

With postmodernity, interest in processes became more pronounced. After an action, after any ephemeral manifestation, what remains is the document as a record of a working process. This interest in processes, in the day-to-day, led an artist like Joan Cardells to praise the absorbed, almost ritualistic efforts of artisans or amateur painters without pretensions.

Miquel Ponce offers us a glimpse into his working processes with "El cub." He presents this project as a challenge regarding the space, as an installation for a specific location that includes finished pieces - which have their own artistic entity - and elements of tests and experiments with various materials typically associated with sketches and preparatory work. These elements are arranged within the cube, taking into account the specific characteristics of the space, seeking the boundaries to define a space that is not physical but metaphysical, exploring the conditions of the possibility of the existence of art itself.

Considering the speculative nature of the glass cube, the installation offers a fleeting look into the artist's studio, constituting a simulated scene, like a theatrical set that incorporates elements of the stage machinery. It is a simulation that allows glimpses into the intricacies of work and transforms the project into a work of art, something characteristic of Ponce's work. Furthermore, in a certain sense, there is a "Deleuzian fold" when the artist presents a staging of his work process as art.

Among the many interpretations offered by Miquel Ponce's work, it is worth highlighting the notion of an essay as a playing field, as he himself suggests, and remembering that the concept of play, as proposed by Friedrich Schiller in his "Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man" (1794), has been crucial from the beginning in the development of modern art. Schiller proposed that in the dialectical ascent to the purest form of beauty, the "form of a form," art must free itself from the mimetic reproduction of natural forms and play with the forms inherent in the language of art. Abstract art produces purer forms than the imitative. But when the artist engages in play and allows themselves to be guided by the forms of their visual language without seeking a definitive form - as Ponce does - they approach the highest form of beauty, for the form of a form contains within itself all possible forms; that is, it defines the conditions of possibility for the existence of a form.

Moreover, it is stimulating to identify in Ponce's work a wide and varied range of sincere and unbiased references to different artists who genuinely interest him. In formal terms, we can establish a connection with Valencian artists such as Amparo Tormo, Ángel Macip, or Jorge Carla. In the background, one can sense the influence of authors from the Basque school of the 1990s, such as Txomin Badiola, Peio Irazu, Jon Mikel Euba, or Francisco Ruíz Infante; even a certain distant resonance with Sergio Prego. But there are also traces of Catalan artist Miquel Mont and the black and white paintings of Miguel Ángel Campano. Additionally, we see the weight of international artists like Robert Ryman, Ad Reinhardt, or Imi Knoebel, for example, and in the way of working with materials, a kinship with some abstract painters of the 1960s like Gerardo Rueda or Rafael Canogar; even the raw power of Manolo Millares emerges in the distance.

In his "essay on space," Miquel Ponce presents his work as an exercise and plays with the various meanings and nuances of the word "essay" to define the best possible way to intervene in the space of the Muvim cube, to represent his concerns, and to integrate the space into the artwork itself. The exercise is reflective and does not aim to provide a single definitive solution. A musician, an actor, or anyone knows that sometimes the rehearsal is better than the final performance. The paradox is that, despite the effort to explore the suggestive provisional nature of things, Miquel Ponce's work has the same composure with which, for example, an apple falls from a tree.

Boye Llorens Peters